UK Legislation and the Transition to a Republic by Barbados

19 October 2021

Plans by Barbados to become a republic have attracted some remarkably ill-informed international coverage. ‘Barbados to Quit British Commonwealth’ claimed the South Atlantic MercoPress agency. Meanwhile, an opinion piece in a UK newspaper described the move as ‘another example of “Global Britain” losing its grip’. The first suggestion is palpably wrong – not only does Barbados have no plans to leave the Commonwealth, it will not even have to reapply for membership. The second is at least arguable although, ostensibly, the move has very little to do with the UK.

The decision to become a republic and the legislation necessary to enact the change are entirely matters for Barbados itself. The government of Mia Mottley has adopted a two-stage approach to the issue, with a swift move to a republic on 30 November, followed by a consultation process leading to a new constitution. This way, it avoids the risk of disagreements about the broader shape of the constitution delaying the achievement of republican status. The first stage was secured on 30 September with the passage through the Barbados Parliament of the Constitution (Amendment) Bill 2021, which essentially transferred the functions and powers of the Barbados Governor General (the Queen’s representative on the island, nominated by the prime minister of Barbados) to the new President of the republic.

Yes – the British government will have to pass consequential legislation of its own as it has done on previous occasions when Commonwealth Realms have become republics. But crucially, this is necessary in order to avoid any confusion in its own domestic law rather than to give effect to a republic in Barbados. The last time it passed a similar bill was the Mauritius Republic Act 1992. The key clause of its extremely short text stipulates that any relevant UK act or instrument would ‘have the same operation in relation to Mauritius, and persons and things belonging to or connected with Mauritius, as it would have had… if Mauritius had not become a republic.’ Moving its second reading, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Mark Lennox-Boyd, noted that it sought ‘essentially to ensure that the operation of our existing law in relation to Mauritius is not affected by the change of status’. He was at pains to stress that, ‘The decision to become a republic was, of course, for the Government of Mauritius to take and did not in any way require the concurrence of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom.’

This point had been noted repeatedly within Whitehall in the past. A briefing paper prepared by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) Commonwealth Coordination Department in February 1969, at a time when Guyana was preparing to transition to a republic, noted, ‘It should be borne in mind that the question of whether a monarchical country becomes a republic lies entirely within its own competence and is one in which Britain has no particular standing’ [Coombe to Sankey, 27 February, 1969, FCO 63/114].

The fact that UK consequential legislation in no sense enacted the transition from a Realm to a Republic meant that the British government was relatively relaxed about its timing. In 1976, when Trinidad and Tobago was about to become a republic, the FCO told the UK high commission there, ‘While it is desirable that this [UK] Legislation should coincide with the entry into force of the new Constitution, this is, in fact, not essential and similar bills relating to Guyana and Malta both had retro-active effect’ [Preston to Diggines, 8 March 1976, FCO 63/1431].

A couple of factors mean that legislating on this issue in the UK will be even simpler in the case of Barbados than it had been in the past. The first relates to a change of rules within the intergovernmental Commonwealth. Before 2007, a Realm transitioning to a Republic had to reapply for Commonwealth membership. While this was largely a formality, it was necessary for the outcome to be known before the UK could draft its own legislation, as it would have practical implications, particularly on the question of whether the country’s citizens resident in the UK had the right to vote. The communiqué of the 2007 Commonwealth heads of government meeting in Kampala signalled that the organisation no longer required a member dropping the Queen as head of state to reapply. Barbados will be the first Realm to transition to republican status since this change was announced.

Secondly, in the UK Acts for Trinidad and Tobago in 1976 and Mauritius in 1992, the only specific area dealt with in any detail related to the desire by both countries to retain appeals to the UK Privy Council after republican status had been achieved. Hence, for example, in the case of the former, the UK Act stipulated that, ‘Her Majesty may by Order in Council confer on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council such jurisdiction and powers as may be appropriate in cases in which provision is made by the law of Trinidad and Tobago for appeals to the Committee from courts of Trinidad and Tobago’. Barbados, however, abolished appeals to the Privy Council in 2005, so presumably no such clause will be necessary in relation to its transition to republican status.

Previous transitions have involved the British government in some more minor tidying up regarding matters of protocol, and the same is likely to be true in the case of Barbados. One such issue relates to the formal credentials of its high commissioner (the term given to ambassadorial representatives between Commonwealth states). In 1976, the FCO noted that the British high commissioner to Trinidad and Tobago had been appointed without formal agreement or credentials, as the posting was from one Realm to another. It pointed out that although the transition to a Republic would not invalidate that appointment, the British high commissioner would need formal credentials (a ‘Letter of Commission’) from the Queen to the new President of Trinidad and Tobago. Likewise, the high commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago in London would need to present the Queen with credentials signed by their President. The transitions from Realm to republic in Sri Lanka in 1972 and Malta in 1974 again suggest that UK was relaxed about the timing of all this. The FCO told the British high commission in Trinidad and Tobago ‘our High Commissioner in Colombo presented credentials a couple of months after the Republic (his counterpart in London ten months after) and our High Commissioner in Valletta presented his four months after (and his counterpart in London seven months after)’ [Martin to Diggines 26 March 1976, FCO 63/1431]. Nevertheless, similar formalities will have to be observed when Barbados becomes a republic. Indeed, changes will have to be made in the protocols governing relations between Barbados and other Commonwealth Realms. In Canada, for example, the process for formally receiving newly-appointed high commissioners from other Realms differs from that applied to those from Commonwealth republics.

Finally, there is a broader point which emerges from the UK files on earlier transitions to republican status. While official doctrine holds that the Queen is quite separately and equally sovereign of the United Kingdom and of her other Realms, that did not stop British officials worrying that she might in some way be embarrassed (and hence UK national prestige somehow undermined) by developments elsewhere in the Commonwealth. They were not, on the whole, especially concerned by the rise of republicanism per se. From the 1960s onwards, London increasingly saw this as a natural and inevitable process, one that might actually improve the UK’s relations with the Commonwealth Caribbean by removing any suspicion that Britain was using the monarchy to maintain neo-colonial influence. They did, however, worry about the mechanics of severing links with the Crown, and they were particularly anxious that formal conventions should be rigorously observed. These began with the government concerned informing the Queen, via the Governor General, of their intention to become a republic. Thereafter, London was keen to know as much as possible about the timing of subsequent moves by the country concerned so that it could coordinate its own response. Its ability to obtain information about these matters was supposedly limited by a firm expectation that correspondence between the Governor General and the Queen was the Palace’s own private channel of communication with the Realm concerned, and that the British government should not have access to it. Yet from the files on earlier moves towards republican status – and from material located elsewhere in the UK National Archives – it is evident that the Palace was quite willing to share this correspondence with the FCO on a confidential basis. In early March 1976, a senior official at the FCO, R W H du Boulay, wrote to the Queen’s deputy private secretary, Philip Moore, mentioning that Moore had passed him a letter from the Governor General of Trinidad and Tobago outlining progress towards republican status. Du Boulay added,

You mentioned to Stanley yesterday the sensitivity of the letter from the Governor General and we shall ensure that it is destroyed after it has been read by those directly concerned here [Du Boulay to Moore, 2 March 1976, FCO 63/1431].

Despite the obvious constitutional impropriety of this move, only a few days later Moore briefed du Boulay about another letter from the Governor General outlining further steps to be taken in the move towards a republic [Memo by du Boulay, 10 March 1976, FCO 63/1431].

Notwithstanding official doctrine about the equality of the Realms, a combination of history, culture and simple geographical proximity has meant that the Palace and the British government have always enjoyed a very ‘special relationship’. At times this has entailed the sharing of confidential information on other Commonwealth monarchies. This situation is somewhat obscured by continuing official secrecy, which has delayed the release of historical materials charting the relationship between the Governors Generals of the Realms, the Palace and the British government. But it deserves to feature in debates about the relative advantages of Caribbean countries retaining the Crown or becoming republics.

Photo credit: regani.

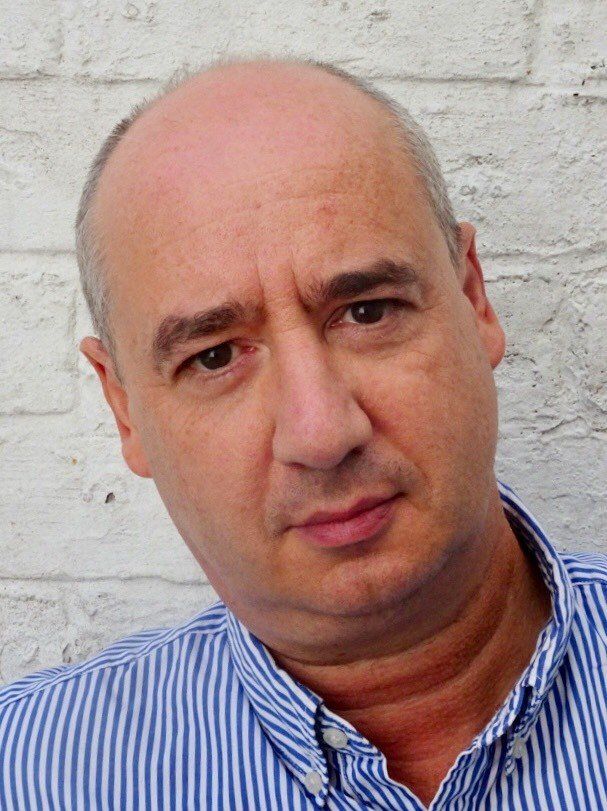

About the author

Philip Murphy

Professor of British and Commonwealth History at the University of London and Director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies. Philip’s many publications include a study of the relationship between the British royal family and the Commonwealth, Monarchy and the End of Empire (2013) and, most recently, The Empire’s New Clothes: The Myth of the Commonwealth (2018). He is also joint editor of the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. Alongside British Imperial History, Philip has a long-standing interest in intelligence history, and in international intelligence links.