Routes to Republicanism in the Caribbean

29 April 2022

Reparations activists protest the royal tour in Jamaica, March 2022. Photo by Advocates Network Jamaica @Advocatesnetja

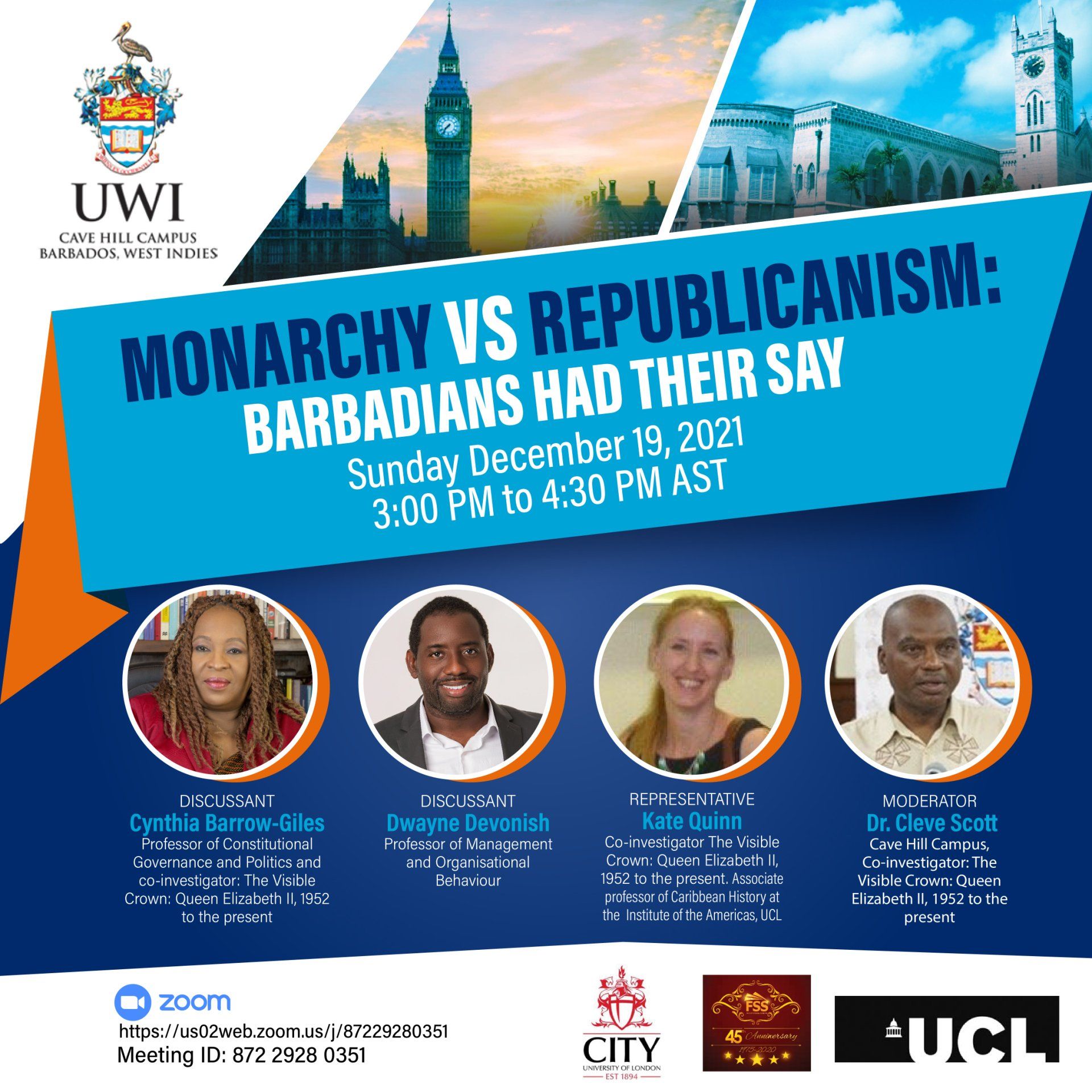

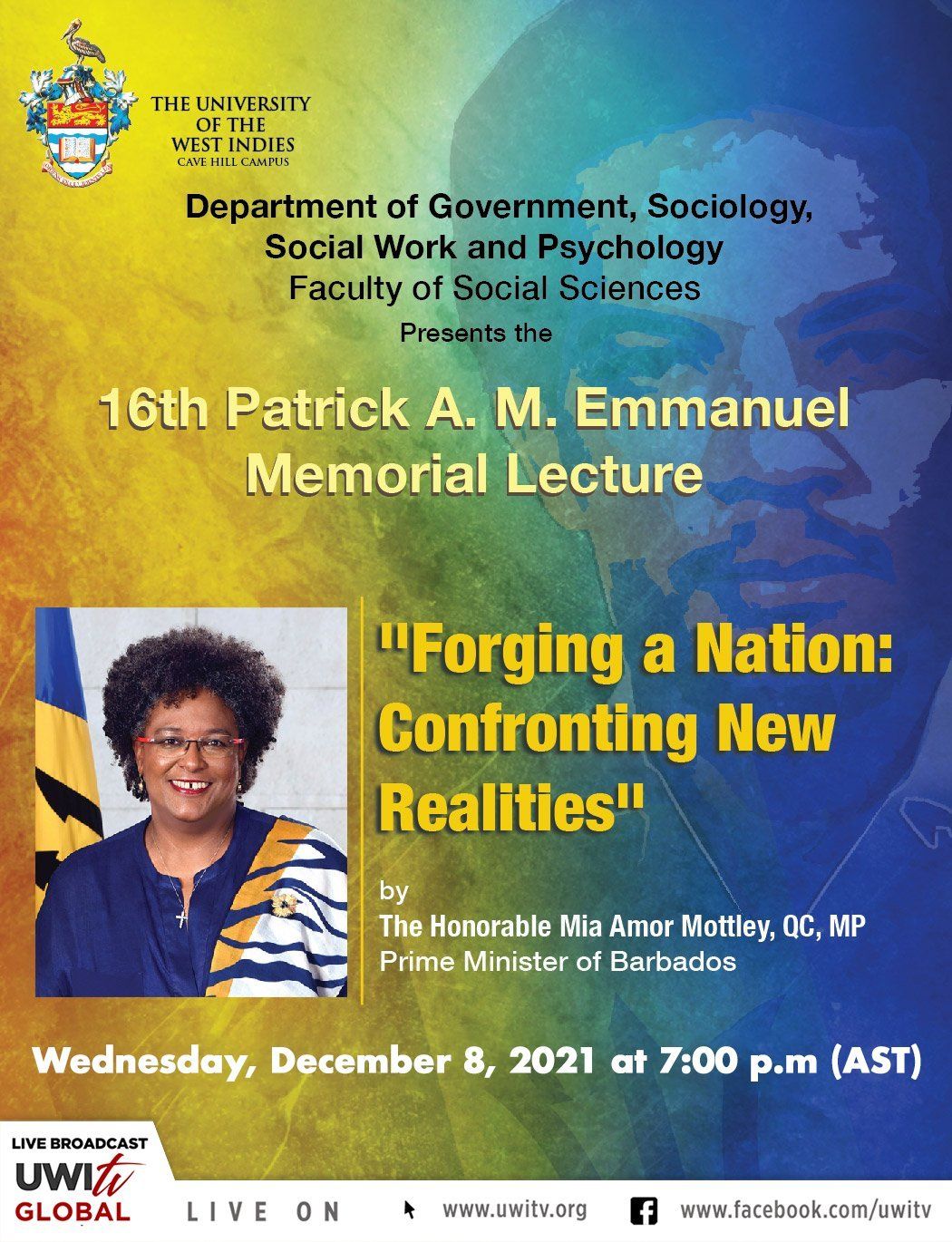

Barbados’ transition to a republic in 2021 raised the question as to whether any of the eight remaining constitutional monarchies in the Anglophone Caribbean would follow suit. Moreover, the highly criticised royal tour by William and Kate in March 2022 prompted calls to remove the Queen in all three of the countries they visited: Belize, Jamaica and the Bahamas. Likewise, Edward and Sophie’s April 2022 Jubilee Tour has encountered calls for reparations and republicanism in Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis, and St Lucia. Media coverage of these events has been full of inaccuracies and misconceptions regarding how different Caribbean countries could become republics. This article seeks to clarify the routes to republicanism for countries and territories in the Anglophone Caribbean.

Firstly, let us consider the states which have already become republics. Dominica is the only nation in the English-speaking Caribbean to have become a republic at the moment of independence in 1978. Meanwhile, Guyana became independent in 1966 and transitioned to a republic in 1970, following a resolution in the National Assembly. Trinidad and Tobago gained independence in 1962 and chose to become a republic in 1976. It is notable that in the three cases, including Barbados, where countries removed the Queen as head of state in the years after independence, this was accomplished through a parliamentary bill.

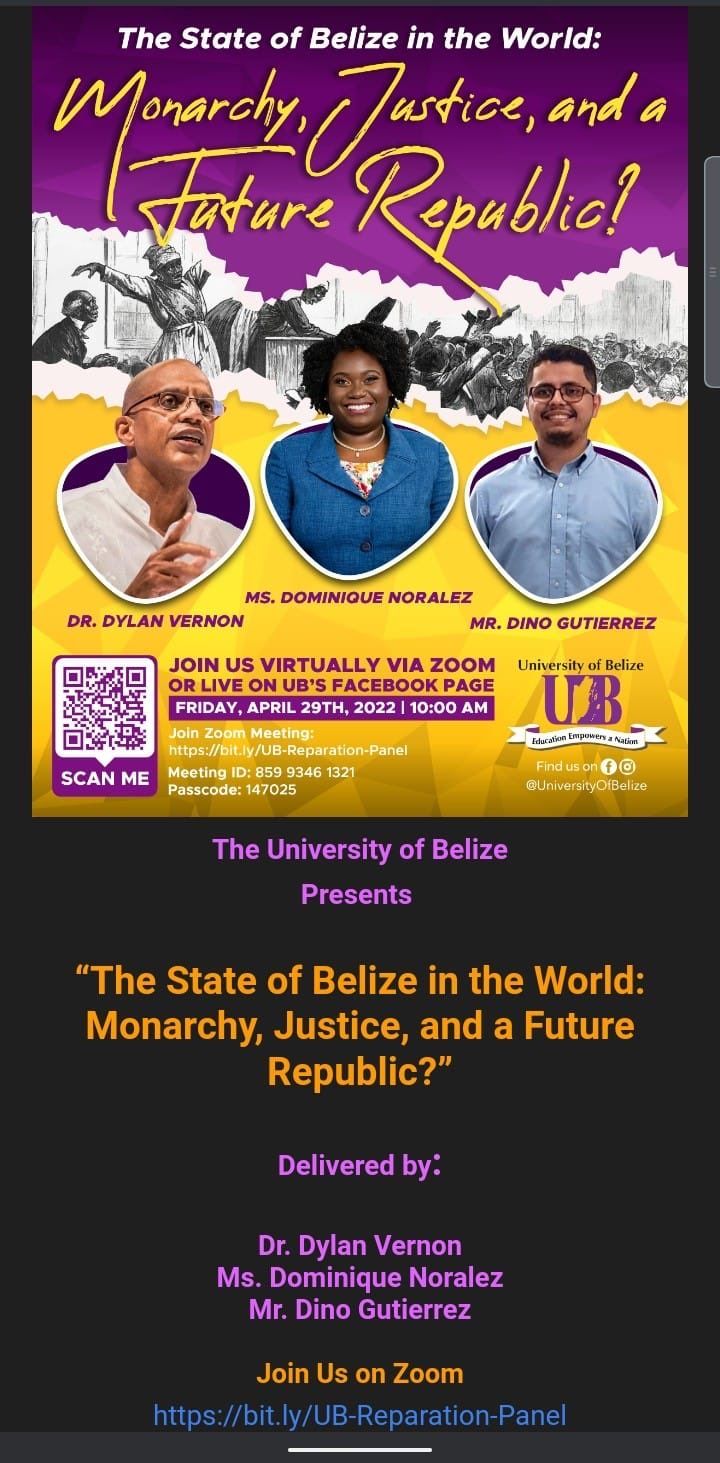

For the remaining constitutional monarchies, only Belize has the ability to abolish the monarchy through the National Assembly. The other seven states need a referendum to make this kind of change to their constitutions.

Furthermore, the requirements for these constitutional referenda differ across the Caribbean countries. In the Bahamas, Jamaica, and St Lucia a simple majority vote is required in a referendum in order to become a republic. However, for St Kitts and Nevis, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Antigua and Barbuda, and Grenada, a two-thirds majority vote is needed, making the transition to republic far more difficult to achieve.

Finally, there are the British Overseas Territories, which retain the Queen as head of state through their more formal ties to the United Kingdom. The Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Turks and Caicos, Montserrat, Anguilla, and Bermuda currently have internal self-government and would need to become independent states in order to remove the British monarchy.

Until now, only St Vincent and the Grenadines have attempted to become a republic via a referendum. In the 2009 referendum, only 45% of voters chose to replace the Queen with a ceremonial president, falling far short of the two-thirds requirement.

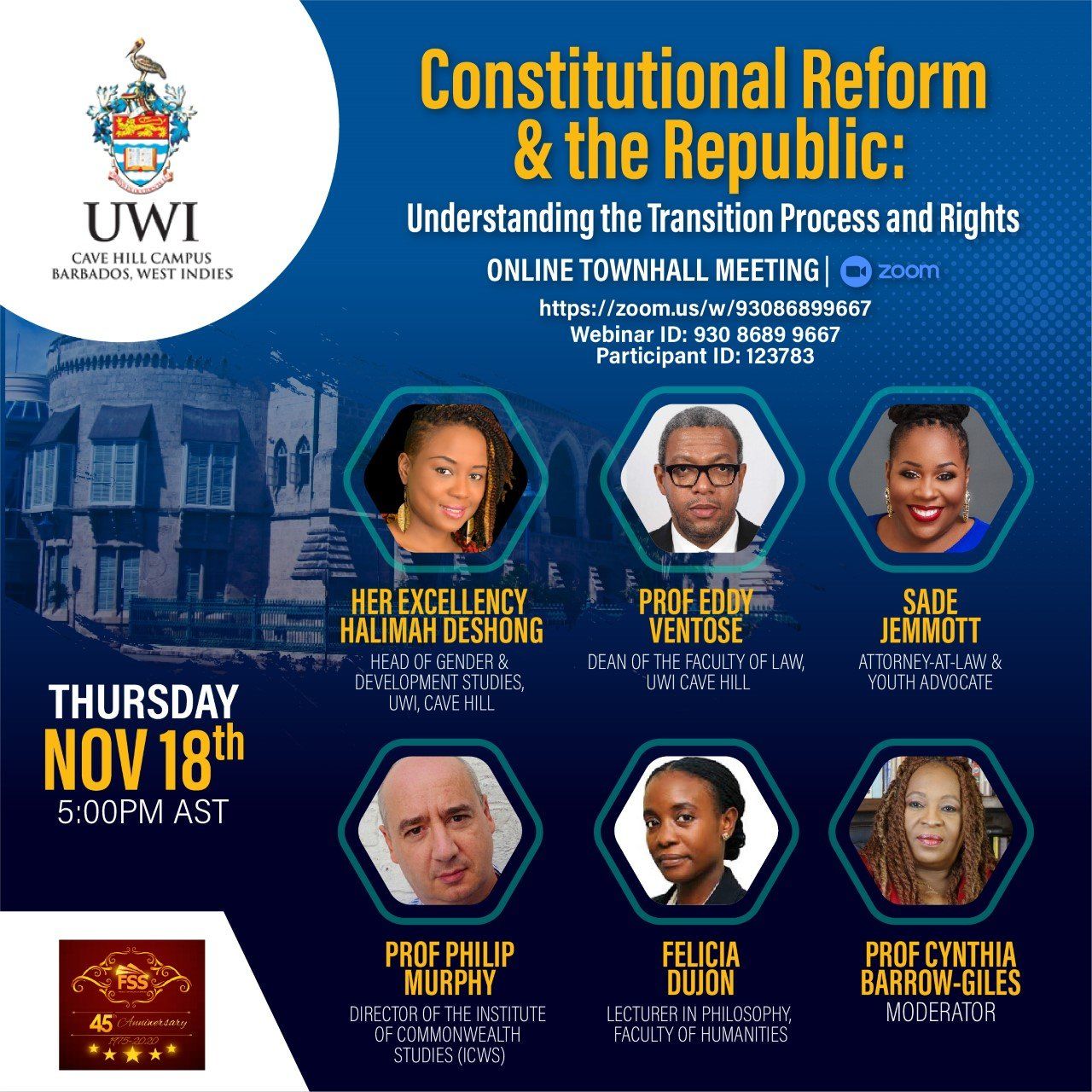

In 2022, political leaders in several Caribbean countries, including Belize and Jamaica, have indicated a wish to remove the Queen as head of state. Perhaps the more pressing question, as raised by constitutional experts like

Professor Cynthia Barrow-Giles, is whether any constitutional amendments would seek to tackle the ‘institutional and cultural malaise in the constitutional and political fabric’ of many Caribbean countries. On independence, former British colonies in the region inherited the so-called Westminster system of government, which maintained rather than disrupted the social, gender, class and racial hierarchies in Caribbean politics and society that had been embedded during the colonial era. Furthermore, reparations advocates across the region have highlighted the

need for reparatory justice in light of Britain, and particularly the monarchy’s, involvement in slavery in the Caribbean. Clearly then, to be more than just symbolic, transitioning to a republic would also need to encompass more lasting changes to democracy and inequality both within Caribbean states and in terms of their relationship to Britain.

About the author

Dr Grace Carrington

Research Fellow at both the UCL Institute of the Americas and the Department of International Politics at City, University of London. Grace’s research interests centre on Caribbean politics in the era of twentieth century decolonisation. She has published on grassroots politics and independence movements in the non-sovereign Caribbean, including Guadeloupe and the British Virgin Islands.