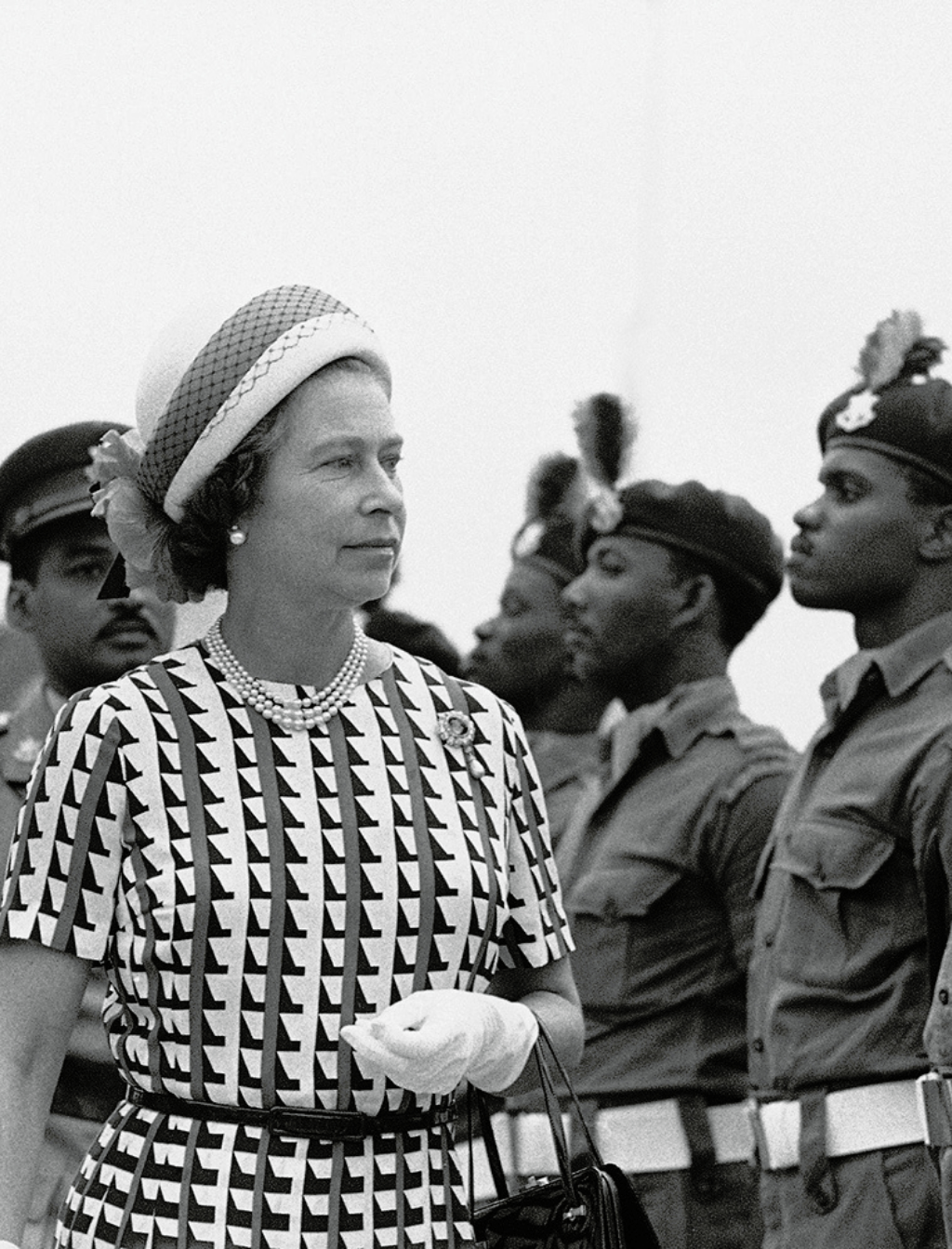

The Queen in Barbados

29 November 2021

The Queen is welcomed by Prime Minister of Barbados, the Honourable Errol W. Barrow on her arrival at Seawell Airport, Barbados, February 1966.

The Queen first visited Barbados in February 1966. She and the Duke of Edinburgh spent two days there. The Queen visited the Queen Elizabeth hospital, and she opened the Farley National Park and the East Coast Road; plaques mark the spots. She visited the University of West Indies and a school. Two-hundred children greeted her with a song: ‘From big to little England/Our gracious Queen you come’. Government officials offered loyal addresses. A red carpet was laid in Bridgetown and the crowds, The Times reported, strained at the police lines. Among the many fluttering Union Jacks, one large red flag with a hammer and a sickle ‘struck a slightly discordant note’ (Telegraph, 15 February 1966). Discordant notes and dissenting voices have always been heard when royals are on progress, as far back as Elizabeth I. Unrest is anticipated, and official reports of tours often express, with great and exaggerated relief, the unanimous and spontaneous joy of cheering crowds.

This royal visit to Barbados formed part of a 5-week tour of the Caribbean and was, apart from Jamaica which the Queen had visited as part of her 1953-4 coronation tour, the first time that Elizabeth II, as Queen, had visited the region. The idea for a Caribbean tour began when Trinidad and Tobago, following independence in August 1962, issued a formal invitation to the Queen. It would not, it was suggested at Royal Visit Committee meetings during 1965, be politic to visit Trinidad and Tobago without also visiting Jamaica, which had also become independent in 1962. Once an invitation from Jamaica had been suggested, and secured (since the Governor General, and not the Palace, had to be seen to initiate royal visits) it was then decided that a tour to as many other Caribbean countries as possible should become a priority for spring 1966. Visits to what the Palace and Whitehall called ‘the monarchies’, it was argued, ‘are of a quite special character’. They ‘play a major part in the maintenance of the Commonwealth association’ (TNA, DO161/220). Visibility was understood to be powerful. ‘I have to be seen to be believed’, Elizabeth II once, apparently, said.

The Caribbean tour began in British Guiana and from there the royal party, sailing in Britannia, would largely follow the line of the islands: Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Dominica, Montserrat, Antigua, Saint Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, a detour north to the Bahamas, and ending in Jamaica. To mark this first Caribbean visit, the Colonial Office produced a commemorative short film which, in particular, emphasized modernity in Barbados – the port, the hospital, the new road: ‘The Royal Tour of the Caribbean’.

Not everyone everywhere was behind such visits; many complained about the cost, or the politics of visible monarchy. Just before the 1966 Caribbean tour, a clipping from the tabloid Sunday Citizen headlined ‘Are these Royal Trips Necessary?’ was circulated among the members of the Royal Visits Committee. It was also around this time that the High Commissioner to Canada advised the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Commonwealth Relations Office, Joe Garner, that visits to Canada be kept to a minimum since the ‘position of the Crown’ in Canada was precarious, and ‘any visit likely to cause controversial issues to flare up’ (TNO, DO161/219, 16 December 1965).

The Royal Visits Committee were aware that British Guiana would become independent at some point during 1966. The possibility that Barbados would also seek independence was raised at one of their meetings late in November 1966, but when this might take place was then unknown (TNA, DO161/219). When Barbados did become independent, on 30 November 1966, the Duke and Duchess of Kent were there. It was the Duke of Kent who handed Barbados’s constitutional instruments of independence to Prime Minister Errol Barrow.

Since 1966, the Queen has visited Barbados on four further occasions: in 1975, 1977 (Silver Jubilee year), 1985 and 1989. This last visit coincided with the 350th anniversary of the Barbados Parliament. In a speech, the Queen referred to a ‘small band of expatriate Englishmen’ who established the House of Assembly in 1639, ‘according to the principles of individual liberty’ (The Times, 10 March 1989).

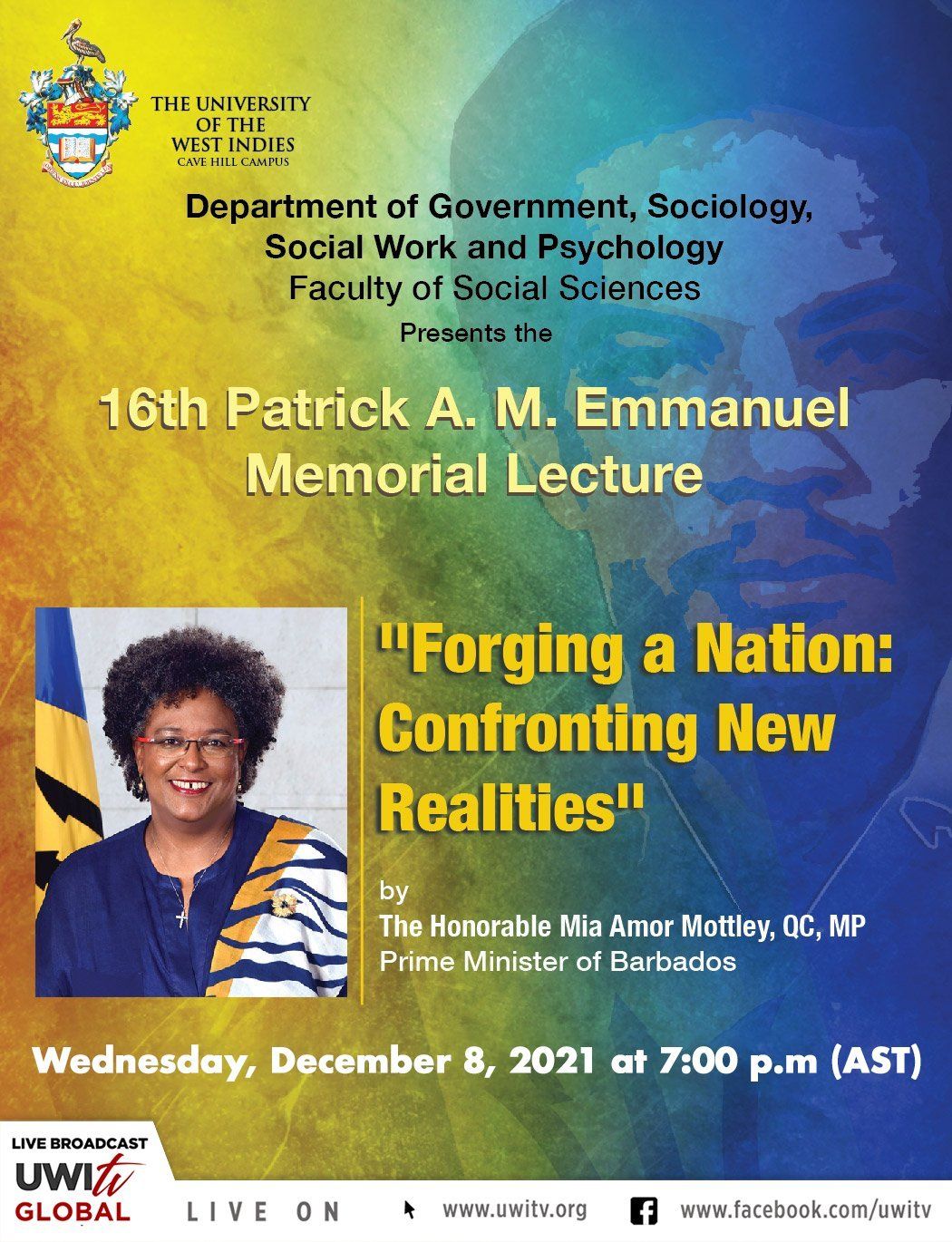

On 30 November 2021, it will be Prince Charles, at the invitation of Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who will officially represent the Queen when Barbados, at the stroke of midnight, becomes a republic. Visible bodies, signs and symbols matter. On Sunday 28 November, at the National Service of Thanksgiving in Bridgetown, Barbados’s new military colours were consecrated and shown to the public for the first time. They replace the old military colours which bore the insignia of Elizabeth II. Last week, Barbados Today reported that a peaceful demonstration was planned for 29 November, to protest against Prince Charles’s presence at the transition ceremony. ‘You are either breaking with the monarchy or you are not breaking with the monarchy. And if you are breaking with the monarchy, then you cannot invite them to be part of that process’, General Secretary of the Caribbean Movement for Peace and Integration David Denny said.

Photo credit: Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021

About the author

Alice Hunt

Associate Professor at the University of Southampton. Alice is a historian of monarchy and royal ceremonies. She has published on Tudor and Stuart monarchy, the English republic, and on the modern royal family.